Editors’ note. For the second article of the The Next Horizon of System Intelligence series, the team from Microsoft Research and University of Illinois Urbana Champaign shares their efforts on defining System Intelligence and their perspective on realizing it through benchmarks as an initial foundation. They are calling for community contributions to enrich existing benchmarks and create new benchmarks that can help AI learn system capabilities.

The term “System Intelligence” has been used to refer to the fundamental leap on AI’s capabilities to design, implement, and operate next-generation computing systems. Realizing system intelligence must unlock AI’s next stage of capabilities, reasoning about architectures and protocols, weighing tradeoffs, applying enduring principles, developing effective abstractions, and more, beyond coding and bug fixing.

Despite the exciting vision of system intelligence, its definition has remained murky, often hindering progress toward its realization. We keep asking ourselves:

- What does it mean to possess system intelligence?

- What are the core system capabilities we want AI to learn?

- To what extent do today’s AI exhibit these capabilities, and how can we measure progress?

In this article, we attempt to answer these essential questions and share our perspectives. We expect to keep refining our answers together with the community. We believe that realizing system intelligence requires the collective efforts of the entire system research community and must be accomplished atop the decades of systems research expertise and experience (much of which today’s AI has never seen in its training data). Meanwhile, this endeavor also helps ourselves reflect on the core values and skill sets that define us as systems researchers.

We welcome your feedback. Follow us on X (@SysIntelligenc) to stay updated on our latest progress in realizing system intelligence.

Measuring System Intelligence

We present a framework to measure different dimensions of system intelligence, which we termed SOAR:

- Scope. The size and complexity of the system that AI can effectively work on.

- Originality. How far AI moves beyond existing baselines to capture novelty and conceptual innovation in system design. i.e., how original its solutions are.

- Autonomy. How independently AI can do research; i.e., how much human guidance is required.

- Rigor. The degree to which the AI system validates its claims, – such as correctness, performance, efficiency, trustworthiness, and reliability – ranging from passing test cases to providing full formal guarantees.

Scope and autonomy reflect an AI system’s capacity for independent research exploration, while originality and rigor capture the novelty and quality of its outputs. We define measurable anchors with scores ranging from 0 to 4 for each dimension.Using the SOAR framework, we can characterize system intelligence across different levels based on their SOAR scores. We analogize levels of system intelligence to the personas of PhD students, as the PhD represents a terminal degree that typically denotes the highest level of academic achievement within a discipline. The following table shows the five levels of system intelligence corresponding to the levels of a PhD student, from a first-year student who focuses on coursework (L1) to a fifth-year student who can formulate new design principles, design novel solutions, and implement and optimize the system artifacts (L5).

| Level | Meaning | SOAR Score | Persona |

| L1 – Basic Knowledge | Knows the terms and core facts | S≥0, O=0, A=0, R=0 | First-year PhD student: passing exams. |

| L2 – Reproducing Known Work | Re-run published results | S≥1, O=0–1, A≥1, R≥1 | Second-year PhD student: reproducing SOSP/OSDI experiments. |

| L3 – Implementation/Optimization | Builds from specs; delivers measurable speedups/fixes | S≥2, O≥2, A≥2, R≥2 | Third-year PhD student: implementing a protocol or optimizing a system component. |

| L4 – Designing Novel Solutions | Creates new abstractions, APIs, or architectures | S≥3, O≥3, A≥3, R≥2 | Fourth-year PhD student: inventing a scheduler, finding/fixing concurrency bugs, diagnosis unknown, ordesigning a new system. |

| L5 – Formulating Design Principles | Distills general, reusable principles, across domains | S=4, O=4, A≥3, R≥3 | Fifth-year PhD student: codifying ideas like the end-to-end argument. |

The table depicts a system intelligence ladder:

- L1 and L2 focus on the foundation, where AI or humans primarily consume and apply existing knowledge by following direct instructions.

- L3 and L4 lead to creation, where the focus shifts toward creating or improving the target systems, demanding deeper reasoning and problem-solving.

- L5 represents abstraction and principles, where the focus moves to theory building and principle discovery, requiring the highest levels of autonomy and insights.

SOAR quantifies system intelligence and provides an intuitive way to track progress. But how do we train AI to achieve system intelligence—much as we teach PhD students—so it can climb toward higher levels and ultimately deliver genuine systems-research innovations?

In this analogy, the student follows a curriculum designed to build specific capabilities. However, only junior PhD students have a structured curriculum. What, then, is the curriculum or the set of capabilities needed for senior PhD students? To answer this, we must first define a comprehensive set of system capabilities: the key competencies that enable effective systems research across diverse domains such as operating systems, cloud infrastructures, and AI systems. With this foundation, we can evaluate which capabilities AI systems already possess and explore how AI can further acquire the rest.

Learning System Capabilities

We categorize key system capabilities into three groups, each encompassing concrete capabilities.

- Technical Mastery: The ability to understand complex systems (e.g., how hardware, OS, and runtime interact), write robust and performant code that handles real workloads, and use tools to instrument, debug, and profile the systems.

- Principled Design Thinking: The ability for architectural thinking beyond implementation, such as abstraction for separation of concerns, principled tradeoff thinking, and system structuring (e.g., decomposing problems into coherent layers or components).

- Empirical and Analytical Reasoning: The ability to understand and explain why systems behave as they do, such as scientific reasoning (formulating hypotheses, running controlled experiments, and interpreting results), analytical modeling (using theory to understand performance and scalability), and failure reasoning (thinking about how systems behave under faults and overload).

In today’s PhD programs, students typically spend five to six years mastering these capabilities. Similarly, achieving system intelligence will require teaching AI to learn all of these capabilities. It is important to note that defining system capabilities is inherently challenging. Our current categorization may not be complete, and we welcome feedback and refinement from the community.

Today’s AI systems already exhibit certain levels of system capabilities. For instance, modern coding agents demonstrate strong implementation skills, as evidenced by their performance on various coding benchmarks (e.g., SWE-Bench and LiveCodeBench). Nevertheless, it is clear that current AI systems have not yet mastered many system capabilities nor achieved full system intelligence.

Why has AI not yet learned the remaining system capabilities? What distinguishes these unmastered capabilities from those it has already learned, such as coding? To explore these questions, let us revisit how AI systems develop coding capabilities and examine whether the same underlying logic can be extended to other system capabilities.

In fact, early AI models were limited to code completion and simple code generation, and were unable to resolve real-world GitHub issues—the best-performing model at the time (Claude 2) solved only about 1.96% of them. During this stage, models were trained primarily on single files and lacked exposure to the broader context of software engineering tasks, such as identifying root causes or iterating through trial and error to reach a final solution. Why can the model do it now (70.60% pass rate on SWE-Bench)? We categorize the key reasons as follows:

- Effective benchmarks. Capabilities are often hard to define and measure. A well-constructed benchmark provides a practical way (concrete tasks) to ground these capabilities. By incorporating diverse, realistic tasks and sound evaluation methodologies, benchmarks like SWE-Bench offer a concrete means to assess model competence and reveal capability gaps. Easy to evaluate is essential as well. Specifically, resolving GitHub issues serves as an effective persona of everyday tasks of software engineers. It is general enough to cover a wide range of coding challenges, draws on readily available real-world data, and supports large-scale evaluation.

- General agents + RL. Agents provide a general and structured process for addressing a type of problem. Given a task, the agents like humans take a series of actions to gather context, reason through possibilities, and refine their understanding. Agents thus enable an autonomous process for expanding and refining the task context during training rollouts. Reinforcement learning can then observe the reasoning, actions, rewards in the trajectory, learn the underlying relationships between problems, actions, and solutions via verifiable signals, and enhance the model accordingly.

In short, benchmarks encode general capabilities through concrete tasks and verifiable, measurable evaluations; agents embody a general process for solving these tasks, unfolding necessary context much like a human would, and RL shapes the model’s ultimate learning.

Benchmarks are essential starting points. We believe that if high-quality benchmarks are provided, AI can effectively learn system capabilities in the same way it learns to understand language or generate code. The main reason AI models do not exhibit these system capabilities is the lack of benchmarks that capture how to reason about architectures and protocols, weigh trade-offs, apply enduring principles, and develop abstractions. Such knowledge is rarely documented and instead exists primarily as tacit expertise in the minds of human experts.

Calling for System Intelligence Benchmarks

We advocate that developing effective benchmarks should be the first step toward enabling AI to learn system capabilities and informing the AI community about what system researchers truly need. Despite the large numbers of AI benchmarks, there are few system-oriented benchmarks available for AI to learn system capabilities, as existing benchmarks fail to capture the inherent complexity of system research.

We call for a community effort to develop comprehensive system-intelligence benchmarks. We expect an effective system-intelligence benchmark to have the following properties:

- Meaningful to the system research community. The benchmark should target real-world workloads, use widely adopted open-source systems, and address well known issues. The benchmark results produced by AI models and agents can directly benefit the target systems.

- Evaluating one or more essential system capabilities. Each capability should be general enough to cover a wide range of diverse system tasks. These are broad capabilities that can be applied to many specific tasks across various areas within the systems domain.

- Easy to scale (optional). The benchmark should have the potential to collect or synthesize large-scale data and artifacts, support easy large-scale evaluation, and target problems not seen by existing AI models.

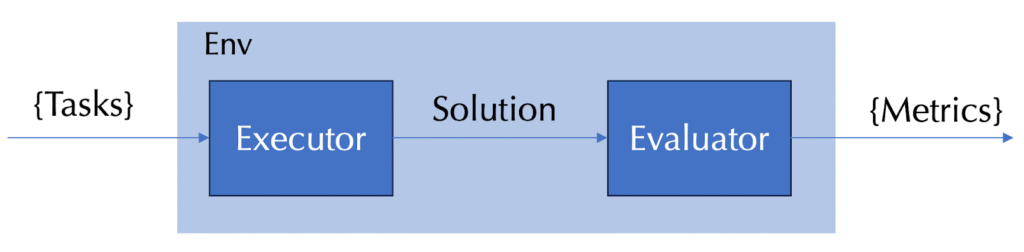

To advance benchmark development, we propose the System Intelligence Benchmark, a modular and extensible framework designed to support diverse research domains and problem types. The framework comprises four abstractions: task set, environment, executor, and evaluator. Each task is associated with a specific environment, wherein the executor generates a solution that is subsequently assessed by the evaluator, which returns the evaluation metrics. This design enables the flexible integration of heterogeneous agents and their systematic evaluation. Additionally, the framework includes built-in executors (agents), evaluators (methodologies and grading rubrics), and tutorials. In an ideal case, users need only supply tasks that represent specific capabilities, select an evaluator, and quickly create and run a new benchmark. The benchmark framework is available on GitHub and is still under development. If you have any questions, feel free to open an issue or contact us directly.

We are also currently working on developing several benchmarks within this framework, as shown in the table below, and will release them in the coming months. Each benchmark assesses specific capabilities across multiple levels within a given research direction. For example, a system modeling benchmark can evaluate system comprehension, abstraction, and potentially tool fluency.

| Benchmarks | Measured Capabilities | Covered Levels |

| System Exam | Technical Mastery: System concepts recall and comprehension | L1 |

| System Lab | Technical Mastery: Setup and comprehension of minimal system, tool fluency for debug, instructed func/component implementation | L1-L3 |

| System Artifact | Technical Mastery: Set up experiment environment and reproduce known research results | L1-L2 |

| System Management | Technical Mastery: System comprehension and tool fluencyEmpirical and Analytical Reasoning: Reasoning with failures | L2-L3 |

| System Modeling | Technical Mastery: System comprehension;Principled Design Thinking: Abstraction (from code to model) | L2-L4 |

| Formal Verification | Technical Mastery: System setup, comprehension and implementation, tool fluencyEmpirical and Analytical Reasoning: Formal reasoning | L2-L4 |

| System Design | Technical Mastery: Specification comprehension, and implementation alignmentPrincipled Design Thinking: Abstraction, principled trade-off thinking, system structuring | L3-L5 |

We welcome community contributions to enrich existing benchmarks (e.g., by adding more exam problems to the System Exam benchmark and more system artifacts to System Artifact and System Modeling benchmark), port your existing benchmarks, and more importantly to create new system intelligence benchmarks with our framework. For detailed instructions, please refer to the repo’s README.md. We believe that such collective community efforts will advance AI to its next level and help realize System Intelligence, unlocking the potential of AI-driven computing system innovations.

If you are interested in contributing or already have good system benchmarks, please let us know. We have set up a slack channel at sys-intelligence.slack.com.

About the Authors

Xuan Feng is a Senior Researcher at Microsoft Research. He is building future agent systems that can bridge the gap between general artificial intelligence and real-world applications.

Peng Cheng is a Partner Research Manager at Microsoft Research. His research interests are in the broad areas of systems and networking, cloud and AI infrastructure, and AI.

Qi Chen is a Principal Researcher at Microsoft Research. She is working on the future AI for systems and also systems for future AI.

Shan Lu is a Senior Principal Research Manager at Microsoft Research and a Professor at University of Chicago. She recently discovered that AI is better than herself at not only writing code but also writing code-correctness proof!

Chieh-Jan Mike Liang is a Principal Researcher at Microsoft Research. He embraces learned intelligence, to optimize the quality and performance of cloud and computing systems.

Bogdan Alexandru Stoica is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, working on improving systems reliability and efficiency. He is trying to befriend AI hoping it will not make him irrelevant so soon.

Zhongxin Guo is a Senior Research SDE at Microsoft Research, working on agentic systems. He is building meta-agents to accelerate agent development.

Jiahang Xu is a Research SDE II at Microsoft Research, working on practical prompt optimization techniques for agents. She recently found that LLM can often craft better prompts than human developers.

Tianyin Xu is an associate professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, working on reliable and secure systems. He is confused by AI and wants to keep sane to enjoy systems research.

Lidong Zhou is a CVP of Microsoft and the managing director of Microsoft Research Asia. He develops scalable, reliable, and trustworthy distributed systems. Now he is fascinated about the co-evolution of systems and AI.