Editors’ note: You must remember the widely discussed Barbarians at The Gate article that opened the The Next Horizon of System Intelligence series! For the fourth blog, we welcome back the ADRS team from UC Berkeley to share their recent work that demonstrates how to embrace and utilize AI (as the “barbarians”) to accelerate system performance research.

This post expands our work on AI-Driven Research for Systems (ADRS). We evaluate three open-source frameworks across ten real-world research problems, demonstrating their ability to generate solutions that outperform human experts, including a 13x speedup in load balancing and 35% cost savings in cloud scheduling. Based on these findings, we outline best practices for problem specification, evaluation, and feedback, providing a roadmap for applying these tools effectively.

- Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.14806

- Code: https://github.com/UCB-ADRS/ADRS

- X: https://x.com/ai4research_ucb

- Join our Slack and Discord

Accelerating Discovery: AI-Driven Systems Research

One of the most ambitious goals of artificial intelligence is to automate the scientific discovery process itself, from algorithm design to experiment execution. We argue that computer systems research is uniquely positioned to benefit from this shift. Traditionally, improving performance in these fields relies on the meticulous, human-driven design of algorithms for routing, scheduling, or resource management. However, this is changing. We are moving from treating systems as black boxes (using AI merely to tune configuration knobs) to viewing them as white boxes, where AI tools can rewrite the system code itself. We term this approach AI-Driven Research for Systems (ADRS).

Building on our prior work, this article expands the scope of ADRS by rigorously evaluating multiple frameworks and suggesting best practices for applying them effectively. Our focus here is to determine how to deploy these tools to solve real problems.

To validate the capability of this approach, we test three emerging open-source ADRS frameworks—OpenEvolve, GEPA, and ShinkaEvolve—across ten research tasks. The results confirm that these frameworks can already generate solutions that match or exceed human state-of-the-art, such as a 13x speedup for MoE load balancing and 35% greater savings for cloud costs in job scheduling across spot instances.

- MoE Load Balancing: OpenEvolve discovered an algorithm to rebalance experts across GPUs that is 13x faster than the best-known baseline.

- Cloud Cost Optimization: In a job scheduling problem for spot instances, the AI generated a solution achieving 35% greater savings than an expert-developed baseline.

With the efficacy of these tools established, we turn to best practices. Based on extensive ablation studies, we outline the strategies necessary for success along three critical axes: problem specification (where “less is often more”), evaluation (where the solution is only as good as the verifier), and feedback (where granularity determines convergence).

New Results on Three ADRS Frameworks

To rigorously evaluate the capability of ADRS, we expanded our investigation to three open-source frameworks—GEPA, OpenEvolve, and ShinkaEvolve—on ten real-world research problems across diverse sub-domains, including networking, databases, and core systems. We use GPT-5 and Gemini-3.0, capped at 100 iterations per run to ensure a fair comparison, and provide the specific configs used in the appendix of our paper.

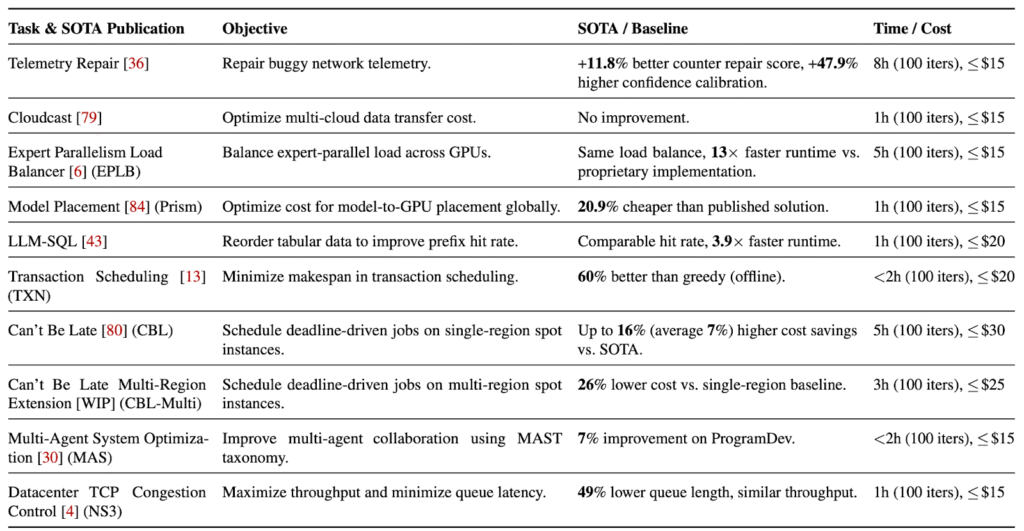

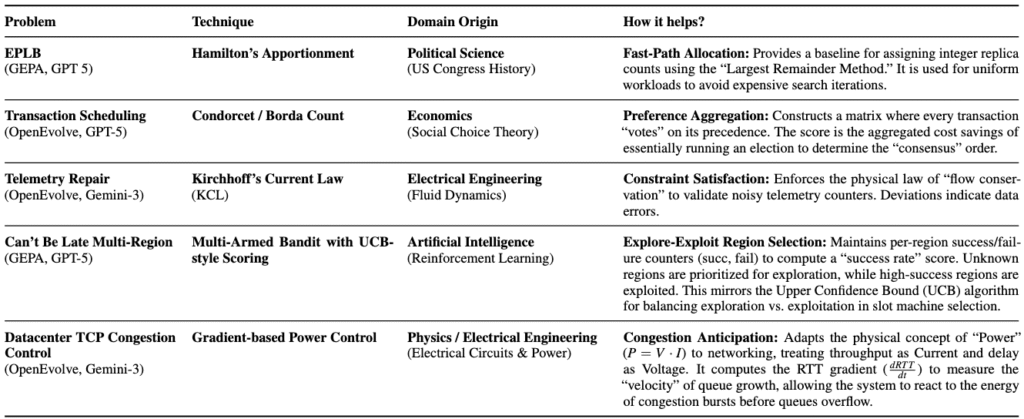

Table 1 presents an overview of selected case studies. In nearly all cases, LLMs were able to discover solutions that outperformed state-of-the-art baselines.

- CBL (Spot Instance Savings) [NSDI ‘24 Outstanding Paper]: Given a job with a deadline, the solution maximizes the use of cheaper spot instances. ADRS improved the SOTA result by up to 35% for a single region.

- CBL-Multi (Multi-Region Spot Savings): An extension of CBL where the policy must also choose migration timing and region placement. The system achieved a 17% improvement over a strong baseline.

- EPLB (MoE Expert Placement): To balance load across GPUs for Mixture-of-Experts inference, ADRS provided a 5x improvement in rebalancing time compared to the best-known proprietary implementation.

- LLM-SQL (KV Cache Optimization) [MLSys ‘25]: The solution reorders table rows and columns to maximize KV cache hit rates. ADRS matched SOTA hit rates while reducing the algorithm’s runtime by 3x.

- TXN (Transaction Scheduling) [VLDB ‘24]: For transaction reordering, the system “rediscovered” the SOTA solution for the online case and improved a strong baseline by 34% for the offline case—a problem for which we are not aware of any published solution.

Most of these solutions were discovered in under 8 hours, at a cost of less than $30. Importantly, the results we’re sharing should be seen as a starting point; as the frameworks and models improve, we expect even more improvements.

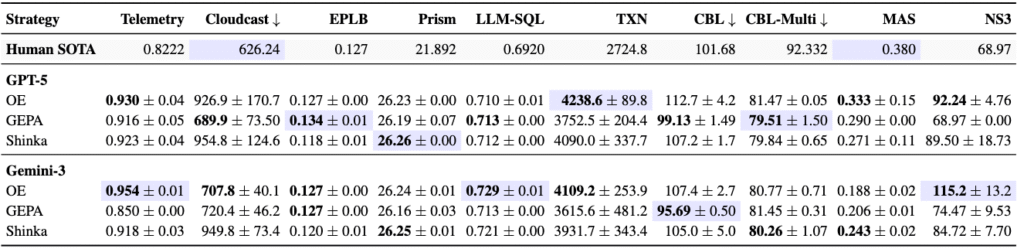

OpenEvolve achieved the highest success rate (Table 2), delivering the best solution in 9 out of 20 total cases (2 models x 10 use cases) and demonstrating the greatest versatility across models. In contrast, the other frameworks showed distinct model sensitivities: GEPA performed significantly better with GPT-5, whereas ShinkaEvolve favored Gemini-3.0.

The key to these successes lies in automating the core research loop: the iterative cycle of designing, implementing, and evaluating solutions. We review AI-Driven Research for Systems (ADRS) approach below.

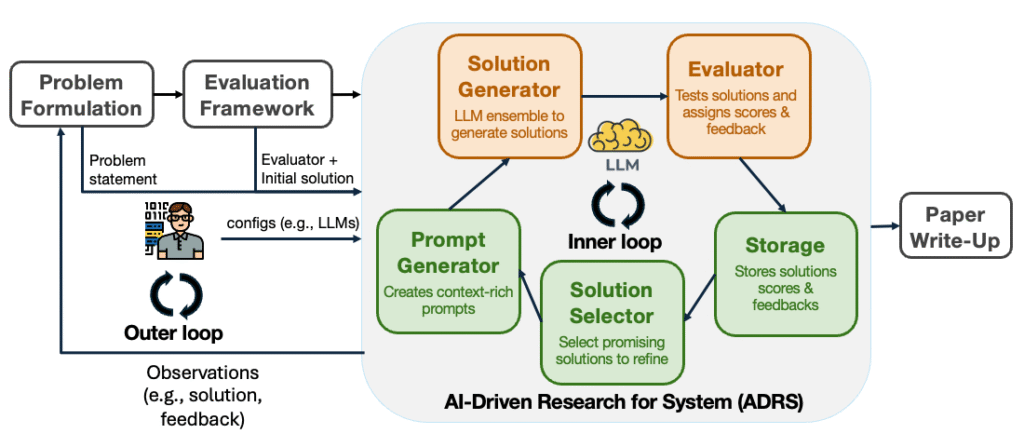

As described in our previous blog post and paper, ADRS automates the core iterative loop of systems research. Traditionally, a researcher follows through five stages (Figure 1):

- Problem Formulation: Define the optimization goal (e.g., improve system throughput).

- Evaluation Framework: Decide which system to use for evaluating the solution, and instrument it. Alternatively, build a new system prototype or simulator.

- Solution: Manually design a new algorithm or technique.

- Evaluation: Implement the solution, run it, and compare it against baselines. Iterate on this solution by going back to stage 3, until a satisfactory solution is found.

- Paper Write-Up: Document the findings.

Researchers typically spend weeks or months cycling between Solution and Evaluation. ADRS automates these specific stages (Figure 2) by using LLMs to iteratively rewrite and refine system code based on performance feedback.

The ADRS architecture comprises five key components.

- Prompt Generator: creates prompts for the LLM. The initial prompt includes a description of the problem and the code of the evaluation framework (e.g., simulator) indicating the code segments that implement the algorithm or the policy to evolve.

- Solution Generator: proposes a new solution by using LLMs to modify the salient parts of the evaluation framework.

- Evaluator: evaluates the proposed solutions, typically by running the evaluation framework on a given set of workloads (e.g., traces, benchmarks).

- Storage: stores all previously generated solutions and their results.

- Solution Selector: chooses a subset of solutions to refine future prompts.

This automated loop is the foundation of several existing implementations, ranging from specialized frameworks like Google’s AlphaEvolve, GEPA, OpenEvolve, and ShinkaEvolve, to workflows using interactive coding assistants like Cursor.

Why Systems Research is a Good Fit for ADRS

We continue to find evidence that ADRS is particularly well-suited to systems performance problems because such problems share one crucial property: verifiability.

The standard AI approach to problem-solving involves two steps:

- Generate: Produce a diverse set of candidate solutions.

- Verify: Evaluate which, if any, satisfy the problem requirements.

The second step is often the bottleneck. In many domains, verifying an answer (e.g., checking if an essay is well-written or if a generated program is bug-free) is as hard as generating it. In systems, however, verification is often straightforward and scalable.

We identify four factors that make this domain ideal for AI-driven exploration:

- Objective Performance Metrics. Unlike subjective domains, systems improvements are measurable. A proposed solution—such as a new scheduling algorithm—can be implemented in a simulator and objectively measured against baselines using metrics like latency, throughput, or cost.

- Preserved Correctness. Performance optimizations rarely alter system semantics. It is often easy to verify mechanically whether a new load balancer still schedules all tasks or if a router forwards all packets.

- Interpretability. The code targeted for evolution is often small—typically the core logic of a resource allocator or scheduler. This allows human researchers to easily audit generated solutions to understand the underlying algorithmic principles.

- Low-Cost Simulation. Systems researchers often use simulators to prototype solutions. This makes it financially and computationally feasible to evaluate thousands of AI-generated candidates (often for under $20) before selecting the best one for real-world deployment.

By automating these bottleneck stages—Solution and Evaluation—without imposing new burdens on other stages, ADRS advances the Pareto frontier of the research process. It allows researchers to focus on high-level design while AI handles the iterative search for efficient algorithms.

Updated Best Practices

Having demonstrated that various ADRS frameworks consistently surpass state-of-the-art solutions, we now focus on effective strategies for applying these frameworks. Drawing from our experiences running these frameworks on a wide range of systems performance problems, we consolidate our findings into actionable best practices categorized across three critical axes: Specifications, Evaluation, and Feedback.

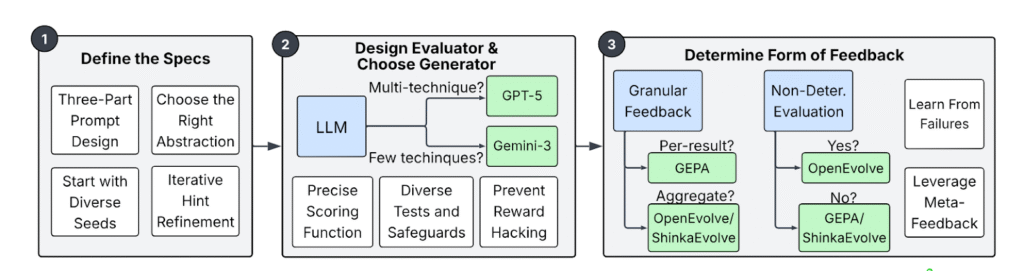

To assist researchers, in applying these frameworks, we provide a workflow guide in Figure 3 that illustrates how these insights integrate into the end-to-end ADRS process. This serves as a practical roadmap for researchers looking to apply these tools to new systems problems.

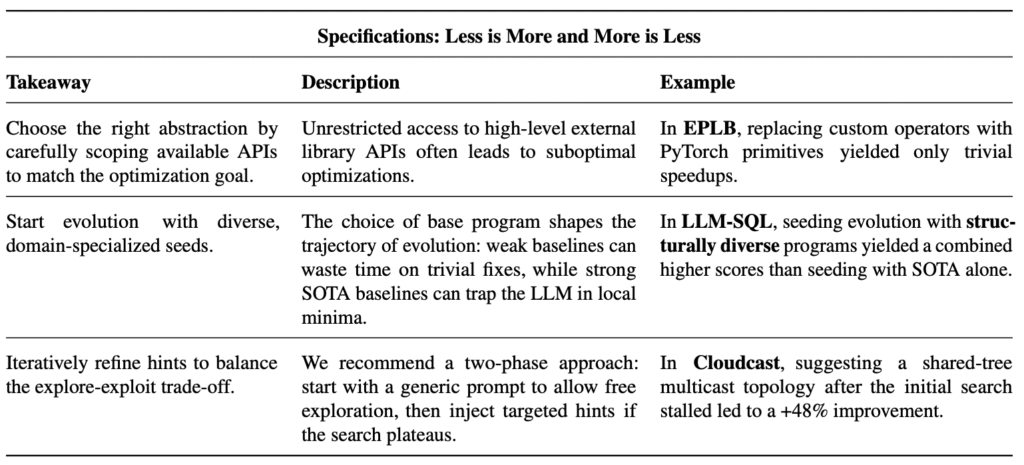

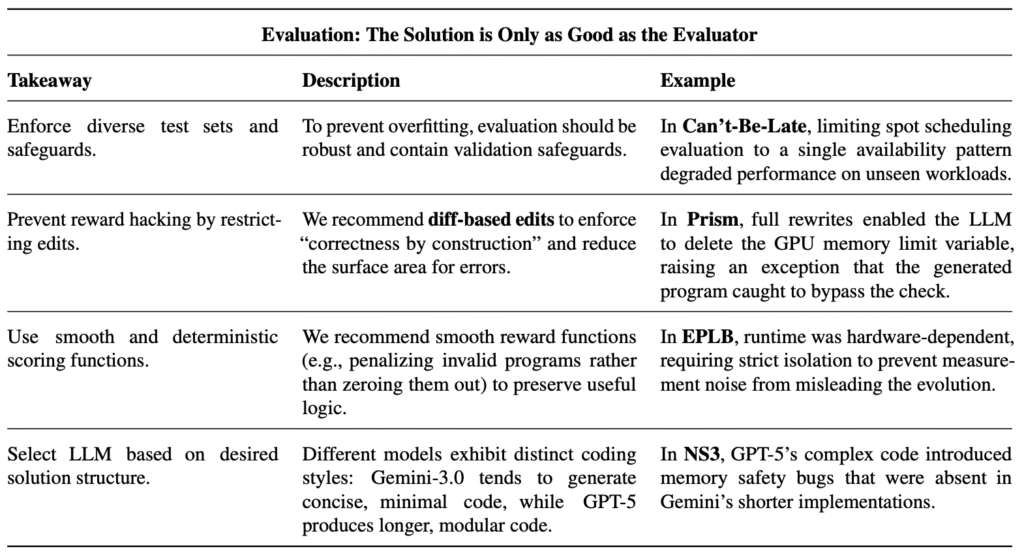

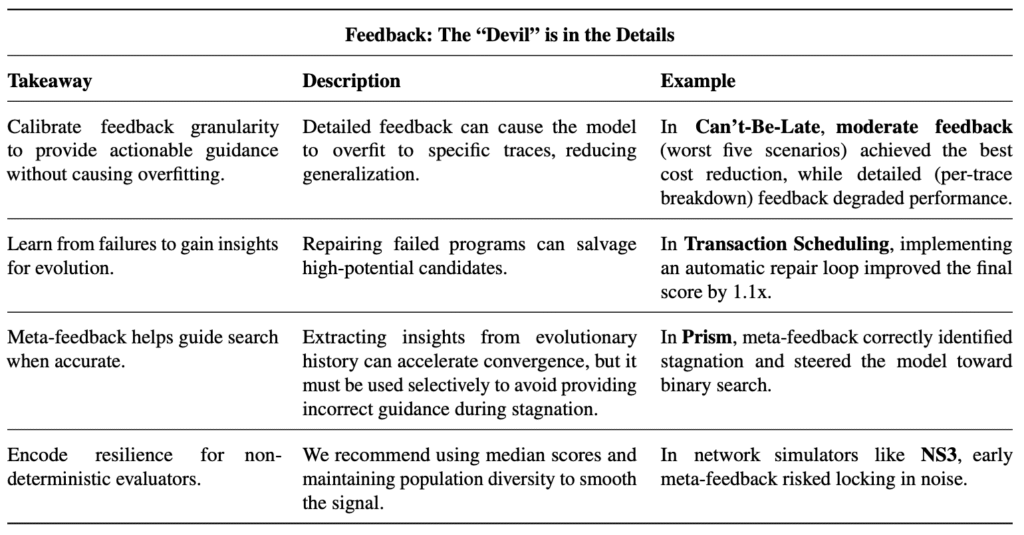

We summarize these strategies in Tables 3, 4, and 5. For Specifications, the way a problem is framed dictates the quality of the solution. Rigorously defined specifications are a prerequisite for effective search. For Evaluation, a flawed evaluator is the primary cause of flawed solutions. The AI will exploit loopholes to maximize its score. Finally, for Feedback, information from the evolution loop determines how quickly the system converges. Provide enough detail to guide the model, but prevent overfitting to specific test cases.

Cross-Domain Discovery

One of the most exciting capabilities of ADRS is its ability to generate solutions by drawing on techniques from different domains. While systems researchers typically specialize in a particular subfield (e.g., networking or databases), LLMs are trained on vast, diverse datasets that span the entire spectrum of human knowledge. This breadth allows ADRS to identify structural parallels between systems performance problems and challenges in unrelated fields—connections that are easily overlooked by experts focused on a single domain. Table 6 provides an overview of cross-domain techniques discovered by ADRS frameworks across our case studies.

We highlight two specific examples where “rediscovering” algorithms from other fields led to significant performance gains:

- EPLB (Expert Parallelism Load Balancing). The core challenge in EPLB is assigning integer replica counts to experts to balance load. An ADRS framework, GEPA, identified that this problem is structurally identical to allocating congressional seats to states based on voting population. Consequently, the tool “rediscovered” Hamilton’s Apportionment method (also known as the Largest Remainder Method), an 18th-century algorithm from political science. By applying this method as a fast-path allocation strategy for uniform workloads, the system avoided expensive search iterations and contributed to a 13x speedup over the baseline.

- TXN (Transaction Scheduling). To minimize conflicts in database transaction scheduling, OpenEvolve leveraged concepts from Social Choice Theory. The generated solution constructs a precedence matrix where transactions effectively “vote” on their preferred execution order based on conflict costs. This mirrors the Condorcet or Borda Count methods used in voting systems. By translating a preference aggregation problem into a database schedule, the system was able to determine an order that minimized global makespan.

Promises and Challenges: Looking Forward

The transition to ADRS offers a significant and much-needed acceleration for systems research. System performance problems are becoming harder: workloads are increasingly heterogeneous, clusters span thousands of servers with diverse accelerators, and hardware generations advance faster than software can adapt. Manually optimizing these cross-layer, rapidly evolving systems is becoming prohibitively expensive.

This is where ADRS offers transformative potential. However, to fully realize this potential, we must understand both where these tools excel today and where they need to evolve.

Where ADRS Excels Today

Our experience suggests that current frameworks are best suited for problems with three key properties:

- Isolated Changes: ADRS works best when improvements are contained within a single component (e.g., a scheduler or load balancer). Problems requiring coordinated changes across multiple distributed protocols(e.g., Paxos or Raft) remain difficult due to context limits and the complexity of multi-file reasoning.

- Reliable Evaluations: The approach requires evaluators that can unambiguously rank solutions. This is straightforward for performance metrics but harder for problems where semantic equivalence is undecidable, such as arbitrary database query rewrites.

- Efficient Evaluations: Since evolution requires thousands of iterations, evaluation must be cheap. Problems requiring hours of GPU time or large-scale training are currently prohibitively expensive for this iterative loop.

Open Challenges

To extend the reach of ADRS, we see several exciting research directions:

- Cascading Evaluators: High-fidelity simulation is slow. Future frameworks should support “cascading” evaluators that progress from fast, coarse-grained cost models to slower, high-fidelity simulators, mirroring how humans prototype quickly before validating precisely.

- Agentic Solution Generators: Current tools struggle with multi-file dependencies. We need “agentic” solution generators capable of navigating and modifying full codebases, understanding cross-layer dependencies, and reasoning coherently across non-contiguous modules.

Preference Learning: Defining numerical weights for trade-offs (e.g., fairness vs. throughput) is difficult. Future systems could leverage preference learning to infer these objectives by observing which solutions researchers accept or reject, rather than requiring explicit mathematical formulation.

A Multiplier for Ingenuity

The evidence is compelling: ADRS can help computer systems research transition from black-box tuning to white-box AI optimization. The tools required for this transformation are already producing results that surpass traditional, human-engineered approaches. And this is only the beginning. As models grow more capable and frameworks evolve, we call on the systems community to embrace this transformation—not as a replacement for human ingenuity, but as a multiplier of it.

What’s Next?

We are actively pursuing research on ADRS. In the coming months, we will release a new framework for optimized search and introduce a standardized leaderboard to benchmark AI performance on systems tasks. We will also continue our blog series and feature success stories from both academia and industry. Stay tuned!

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by gifts from Accenture, AMD, Anyscale, Broadcom Inc., Google, IBM, Intel, Intesa Sanpaolo, Lambda, Mibura Inc, Samsung SDS, and SAP.

The article is edited by Haoran Qiu and Tianyin Xu.